An attorney’s guide to Amended Rule 902 and safely traversing the related dangers

By Adam Bowers, JD.

There has been a seismic shift in the Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE) with some far-reaching implications. A recent amendment to Rule 902 is causing some corporate entities to question whether they should allow self-collection of their own litigation data or if they are required to hire a 3rd-party professional to oversee the task. The good news for those corporations is that the amended rule does not necessitate the use of forensic collection experts, but there are still some very important reasons to consider doing just that.

Introduction

At a minimum, attorneys should understand, and optimally participate in, the identification, preservation, and collection of their clients’ ESI (Electronically Stored Information). This paper provides an overview of self-collection and a cost-benefit analysis of the DIY (do it yourself) model from a lawyer’s perspective, not a marketing perspective. This is an important distinction because doeLEGAL is not a forensic collection company, we offer best-of-breed data collection technologies and partner with clients to ensure they know how to be successful. The intent is to take an honest look at the issues surrounding how corporate clients gather and identify litigation data.

This paper is not to be considered legal advice. If you need legal advice, consult with a licensed attorney. With that said, let’s look at the changes FRE 902 brought to life and its impact on collections.

Dangers of allowing employees to conduct legal holds, manage their own data, and administer a self-collection

With all the new technology now available, it is easy to forget that humans are still part of the litigation equation. One case, in particular, exemplifies just how expensive it can be to allow employees to preserve their own litigation data: GN Netcom, Inc. v. Plantronics, Inc. The case has become so well known in eDiscovery circles, much like Zubulake, that it joins the infamous “single name club” – we call it Plantronics. In this case, a senior member of management instructed his sales team to delete certain emails and other data in direct contradiction to a company-instituted legal hold on those email accounts. The intent of the sales manager was seemingly malicious and the Delaware federal judge was not amused. He sanctioned Plantronics, to the tune of three million USD, plus associated fees and costs. It is important to note that Plantronics was ultimately victorious on the merits of the case, but was still liable for millions in spoliation associated costs: they lost the battle, but won the war. While the Plantronics case serves as an example of intentional destruction of litigation data, there are also less nefarious reasons that employees should not be left to manage their own data preservations or collections.

Before we get too far into the concepts of preservation and collection, let’s define “custodian self-collection” using the two methods used most. One is where the custodians are responsible for the preservation, searching, and identification of their data while IT would do the actual collection (gathering of ESI – Electronically Stored Information). The second is where the custodians are responsible for preserving, searching, identifying, and collecting their own data. Each leads to many of the same challenges and risks, but the first method is far more widely used in business so we will use that as our reference.

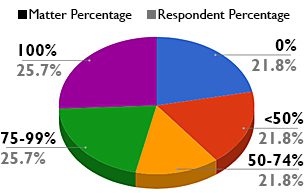

Norton Rose Fulbright’s 2017 Litigation Trends Annual Survey covered the subject in their section on discovery where they asked respondents: In the past 12 months, for what percentage of your matters have you primarily relied upon self-preservation?

Norton Rose Fulbright’s 2017 Litigation Trends Annual Survey covered the subject in their section on discovery where they asked respondents: In the past 12 months, for what percentage of your matters have you primarily relied upon self-preservation?

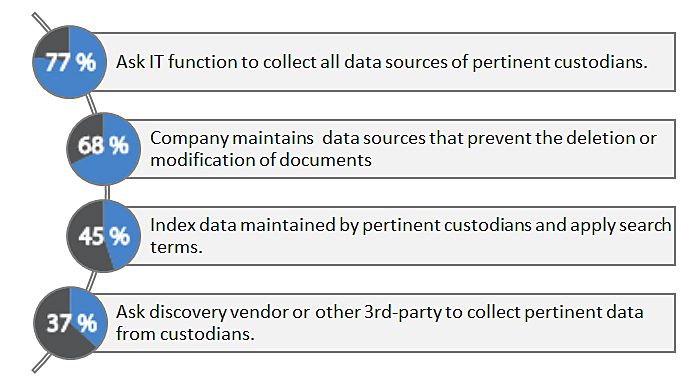

In a recent webcast[1], 62% of the attendees were concerned with spoliation risks associated with custodian self-preservation. However, a survey of corporate counsel, 47% of organizations relied on custodian self-preservation more than 75% of the time. This shows a clear split between what they know is right and doing what’s right. Another question on the Norton Rose Fulbright survey uncovered more about how respondents handled their data preservation: If you do not rely on self-preservation, how do you preserve potentially relevant documents? 77% of respondents who weren’t relying on self-preservation were, at least some of the time, employing a “collect everything” approach to preservation, an approach which creates its own obvious issues such as increased costs, larger volumes of data to review, and potential risk in other legal matters.

Another example of the dangers of custodian self-collection comes from Nat’l Day Laborer Org. v. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency, government employees from several different agencies attempted to compile data in connection with a FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) request. There was a general lack of supervision and the employees were free to search their own email accounts. But several ex-employees’ emails were never searched at all, which prompted Judge Scheindlin to order the parties to meet again and confer to formulate search criteria and procedures. Scheindlin pointed out that there was no clear identification process in place and the employees were directed to identify personally-created data, which was not a normal work duty. In fact, one of the major issues was that those government employees were not even aware as to where their custodial data was being stored so, when they merely searched their shared drives, many records were missed entirely.

Despite having spent thousands of hours and hundreds of thousands of dollars on the exercise, the court opined that “Transparency is indeed expensive, but it pales in comparison to the costs to a democracy of operating behind a veil of secrecy”. Custodian self-collection has long been disfavored by the courts because it is not systematic, repeatable, and defensible. Judge Scheindlin went so far as to say, “Most custodians cannot be ‘trusted’ to run effective searches[…]” This may explain why FRE 902 was amended to require the certification of a collection by a “qualified person”. Attorneys should be involved in all aspects of the preservation and collection of their clients’ litigation-data, no matter who performs the physical collection. But the new FRE 902 does not directly speak to attorney involvement.

I would be remiss if I did not mention that almost a decade ago, the Chancery Court of Delaware had all but placed an outright ban on unsupervised self-collection of employee data. In Roffe v. Eagle Rock Energy GP, LP, et al, C.A. No. 5258-VCL (Del. Ch. Apr. 8, 2010), the Court of Chancery addressed party self-selection of the documents to be produced in litigation. “This is not satisfactory. Attorneys should not rely on their client to search their own e-mail system. There needs to be a lawyer who makes sure the collection is done properly.”

[1] Exterro’s “Examining E-Discovery Statistics: The Zombie Doctrine of Self-Preservation”

Where oh where has my data gone?

The over-collection of litigation data is the norm, and we discussed some of the dangers you face in doing so earlier. Collecting enough is not the same as over-collecting. Steve Bunting, CEO of Bunting Digital Forensics, put it this way, “You never know when a spoliation claim will come up and getting everything up front puts you in a far better position down the road”. By creating a forensic image of a device or server, you may just be capturing data that you did not know you would need later. For instance, imaging a laptop will save the entire hard drive, including something called “free space”. Without getting too technical, free space is the part of a drive that contains deleted items or file fragments. When someone deletes a file, devices will break that file into several pieces and send it to the free space of the hard drive. A skilled forensic expert may be able to retrieve and reconstruct ESI from this free space which could be important if opposing counsel is accusing your client of intentional or negligent spoliation.

So what’s the bottom line here when it comes to self-collection problems? It’s really quite simple: most employees don’t understand what to collect, or where to collect it from. This is where a forensic collections expert can help solve this problem by creating a “data map” to show all the custodial devices (office, mobile, and personal), any instance of third-party data hosting (emails, social media, sales platforms, etc.), and all the internal and external storage locations. This visual depiction can be very useful during a self-collection because it provides a “data treasure map” that can be easily understood and actioned.

Any good attorney must be aware of the human component and safeguard against risks including the intentional deletion of data and the slothfulness of his/her clients’ employees.

What’s the attorney’s role in the process?

While a legal hold is not directly addressed in this paper, it suffers from many of the same issues as a collection, including the identification and supervision that the collection process presents. In short, it is impossible to collect what has not been preserved and it is equally impossible to preserve what has not been identified. With so much at stake, much of the responsibility for preservation and adequate collection practices is being shouldered by the attorney which makes involvement in the process throughout the life cycle of the litigation, crucial to success.

Early in the identification process, a litigation attorney must be vigilant of which custodial data may be involved and where that data is being stored. The attorney must determine the breadth, depth, and reach of the litigation and safeguard any data that may fall within that scope. This exercise is not limited to data that he/she knows to be part of an actual litigation, but extends to data that may be a part of any future litigations. In effect, the FRCP and the FRE make the attorney the fiduciary of litigation data for current or potential future litigations.

Attorneys who are involved in the litigation often do not know exactly what data or evidence may be relevant, so it is reckless to believe that employees in possession of ESI will be able to make this judgment. The best course of action is to meet with opposing counsel and design a legal hold that will reasonably capture as much relevant ESI as possible. This may include scheduled meetings with identified or potential custodians to ensure compliance with legal holds.

It is important to point out that the ABA has expressly recommended that attorneys understand their clients use of technology (Rule 1.1 comment 8). Additionally, most U.S. states have made technology competency a part of their Model Rules of Professional Conduct. However, some of the language used by the states is quite vague and speaks to a standard of care that is akin to avoidance of negligence.

One final area that should be addressed is “chain of custody.” An attorney should maintain a proper, well-documented ESI chain of custody which starts with the identification and collection of the litigation data and continue throughout the life of the litigation. Any alteration to the original data that is collected will be traced back to the party that was in control of that data, at the time of the alteration. A comparison of the hash values is a quick and easy way to test if a document has been altered, but this also presumes that metadata has been preserved and collected. Treat ESI like you would any other piece of trial evidence. It is important to know and understand the life cycle of all trial evidence and to maintain accurate records of your efforts.

Conclusion

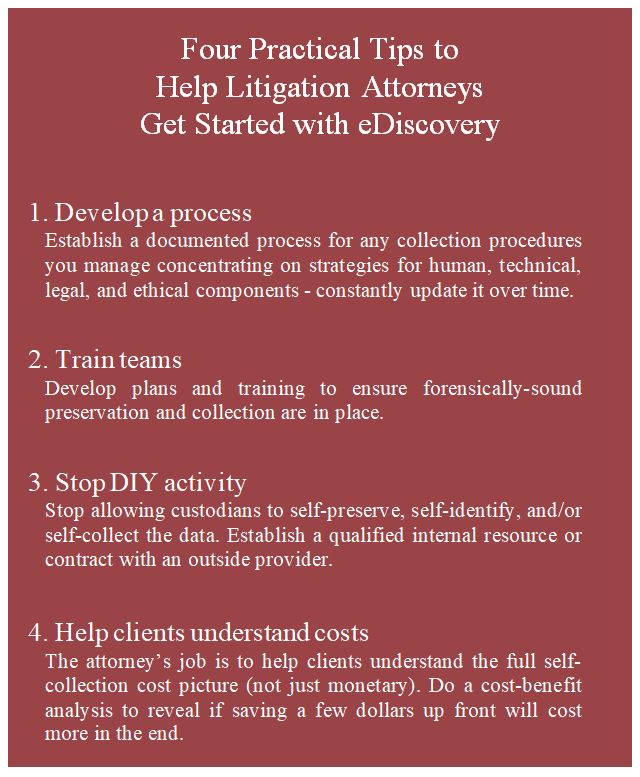

Investing money upfront to hire a professional or train internal employees to perform forensically sound collections can stave off future pitfalls associated with the use and review of litigation data. Keeping in mind that the most expensive aspect of an eDiscovery project is the time that attorneys or paralegals spend reviewing the ESI that was collected, it becomes even more apparent that investing in proper collection practices is cost-justified.

There are many moving parts to eDiscovery: Human, technical, legal, and ethical. By ensuring that proper legal holds and collection practices are followed, an attorney may be best positioned to safeguard their client from possible sanctions for spoliation and reduce the resources spent by litigation support and review professionals. Whatever the amount of money that might be saved by following a DIY model of self-collection, this will certainly be outweighed by extra resources spent by litigation support professionals, reviewing attorneys, and the need to hire trial experts to authenticate the data collected. The old English sailing proverb, “a stitch in time saves nine,” which loosely means that a timely effort today will prevent more work later, is still applicable to modern-day litigation practices.

About the author: Adam Bowers is a former employee of doeLEGAL, an eDiscovery expert, LLM candidate, former business owner, and legal technology practitioner who helps law firms and attorneys navigate the complex world of discovery.

To learn more, visit: doelegal.com/ediscovery-litigation, speak to a trusted advisor – call 1.302.798.7500, or email info@doelegal.com.

About doeLEGAL

doeLEGAL is built on a promise to provide “Smart data, intelligently delivered.” Our software and services help corporate legal departments and law firms efficiently manage operations with up-to-date, insightful data that help teams make confident decisions. We facilitate anytime, anywhere control over cases and costs with advanced management tools and elevated support to generate insights and drive successful outcomes.